Seattle’s First Railroad

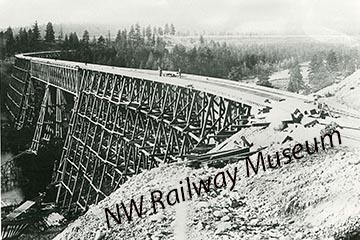

In 1873, the Northern Pacific Railway (NP) chose Tacoma (Washington Territory) as the western terminus of its transcontinental railway. The decision followed many years of active campaigning by community leaders in Tacoma, Seattle, and Bellingham. All understood the potential economic boom that could occur at the west end of a transcontinental railroad.

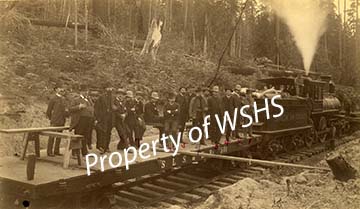

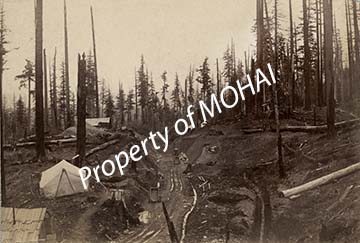

On May 1, 1874, Seattle citizens turned out to start building the Seattle and Walla Walla Railroad, Seattle’s first railroad. Although its purpose was to haul coal from mines to steam ships, the company had grand aspirations of completing the line all the way to Walla Walla.

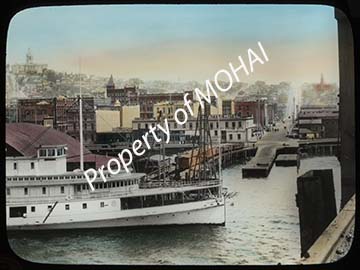

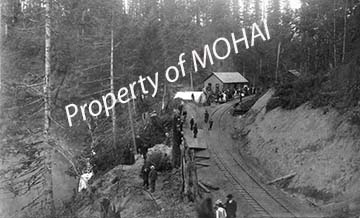

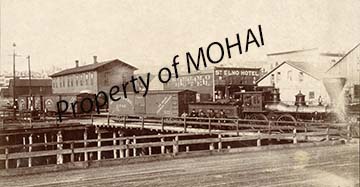

The line was originally five miles long and ran from Steele’s landing on the Duwamish River to Renton. James Colman, of Colman dock fame, hired workers to extend the line to Newcastle. It would eventually be twenty-one miles long and run between South King County mines and Elliot Bay piers. In the early 1880s the railroad was purchased and renamed the Columbia and Puget Sound Railway.

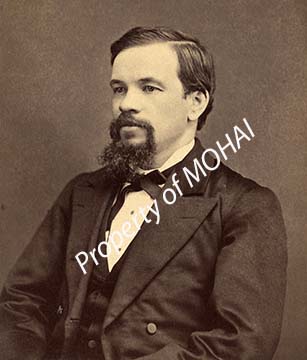

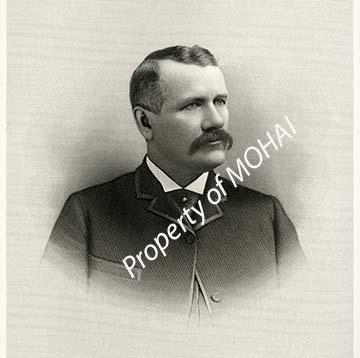

While the Seattle and Walla Walla had a positive impact on Seattle, it did not accomplish the goal of capturing the bounty of transcontinental commerce. Enter Burke and Gilman.

Some would dispute the proclamation that Seattle & Walla Walla was Seattle’s first railroad. Two years earlier, Seattle Coal and Transportation Company (SC&T) began hauling coal between a dock on Lake Union and coal bunkers on Elliot Bay. Without aspirations of eastern connections, and because it existed at the time the NP chose Tacoma over Seattle, the SC&T was never regarded as the means to punish or discredit the NP, or it’s choice of Tacoma.